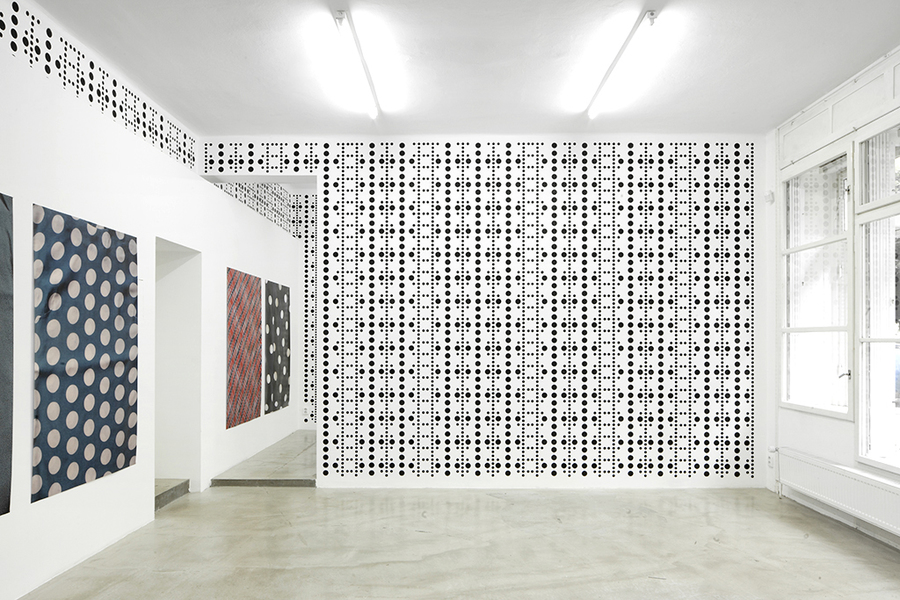

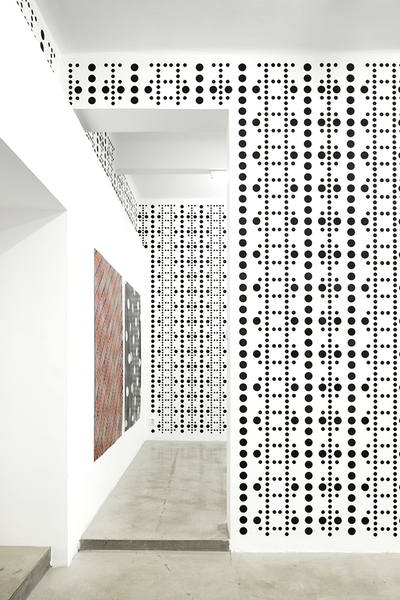

The following text is to be read as a sample book of texts similar to a sample book of fabrics, cloths, a sample book of touches and sensations. It refers to texts dealing with the relation of the tactile and the optical and with the difference between the tactile and the haptic. These texts are interwoven with the question of the relation between tactile and optical experience, the nature of textile and photography, the possibility of touching things by the eyes. The more apparent the seams between the individual texts, the more opaque the proportion between the obverse and the reverse, the historical and the timeless. The present text-sampler shall have the features of both embroidery and patchwork as conceived by Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari.[1] They describe “the distinction […] between embroidery, with its central theme or motif, and patchwork, with its piece-by-piece construction, its infinite, successive additions of fabric. Of course, embroidery’s variables and constants, fixed and mobile elements, may be of extraordinary complexity. Patchwork, for its part, may display equivalents to themes, symmetries, and resonance that approximate it to embroidery. But the fact remains that its place is not at all constituted in the same way: there is no center; its basic motif (“block“) is composed of a single element; the recurrence of this element frees uniquely rhythmic values distinct from the harmonies of embroidery (in particular, in “crazy” patchwork, which fits together pieces of varying size, shape, and color, and plays on the texture of the fabrics).”[2] This text is to be read as a manual for a tactile exercise and its performance, a haptic exercise and an exercise in looking closely, an exercise in touching by the eyes. At the same time, it does not deny the evident inability of text to mediate the experience of touch. In spite of the tactile vocabulary being not in the least poor, it definitely does not have the necessary precision or urgency. The long history of writing on the sense of touch and touching does not lead to a final clarification of the situation but rather unfolds and folds old unclarities turned new. To prove this point, let me mention two statements from different epochs and contexts: according to Aristotle, it is not clear whether touch is one sense or rather several senses that can differentiate between several perceptions such as “hot and cold, dry and wet, hard and soft and similar qualities.”[3] László Moholy-Nagy documents the same thesis on another scale: “smooth, rough, hard, soft, fluted, ribbed, embossed.”[4] “It is surely the sense of touch,” he argues, “that may be divided up into a greater number of separate qualities of sensations […]: pressure, temperature, vibration.”[5] Aristotle grants the sense of touch a special position among other senses which are conditioned by it in a certain way: “Without touch there can be no other sense.”[6] The vibrations of this thesis can be traced in the art history of the early 20th century. The duality of the tactile and the optical was explicated by Alois Riegl in his book Die spätrömische Kunstindustrie published in 1901.[7] Whereas the perception of a surface proceeds in a purely optical regime according to Riegl’s “empirical observation,” the third dimension, depth, is conditioned by a tactile experience with a solid, impenetrable surface. This “tactile memory” then sets out on a “complex path of the mental process”[8] by which vision releases itself from an immediate dependence on the sense of touch while embracing it in a certain way. Riegl’s definition of the tactile and the optical thus involves certain ambivalence. Riegl presents his notion of these two terms on the backdrop of the developmental model of ancient art. He describes the shift from Egyptian art to Roman art as a shit from the tactile to the optical, from surface to space, from the whole to parts. That naturally does not mean that Riegl denies Egyptian art any optical qualities. However, they are nahsichtig. Nahsicht, a close look, is still close to the tactile and reveals a world of symmetry and clear outlines, a world without shadows and without a horizon. When the close look gradually frees itself from the tactile sphere, it becomes Fernsicht, a distant look. Riegl’s theory can be briefly summed up in the following way: “Just as tactility is the necessary precursor to an optical mode in the history of art, so, too, touch is a physiological precursor to vision within the framework of our perception of space.”[9] Similarly to Riegl, in his Principles of Art History (Kunstgeschichtliche Grundbegriffe) from 1915, Heinrich Wölfflin links the relation between the tactile and the visual with a certain developmental scheme: from line to surface, from drawing to painting, from Dürer to Rembrandt, ”the tactile picture has become the visual picture – the most decisive revolution which art history knows.”[10] However, he does not ascribe a definitive teleological validity to this development when he says that “the purely visual apprehension of the world is one possibility, but no more. By the side of this there will always arise the need for a type of art which does not merely catch the moving appearance of the world, but tries to do justice to being as revealed by tactile experiences.”[11] According to Wölfflin, the two ways of relating to the world are connected in a rather complex way that almost has “tactical” qualities: “It is no contradiction if even here the visual sense seems nourished by the tactile sense – that […] tactile sense which relishes the kind of surface, the different skin of things. […]From differently orientated interests in the world, each time a new beauty comes to birth.”[12] Wölfflin’s approach seems to reverberate in the book The New Vision: From Material to Architecture where Moholy-Nagy describes “tactile exercises” that were part of the elementary course at Bauhaus.[13] Within the exercises, the students gathered a great variety of materials to register as many different sensations as possible.[14] They put them together into tactile tables which contained some related and some contrasting tactual sensations. After a shorter or longer period of experimentation they were able to assemble these elements in such a way that they would correspond to a previously planned expression.[15] That was supposed to produce a “new tactile value.”[16] Besides, Moholy-Nagy has observed that “intensive work with material contributes to a better understanding of one’s feelings.”[17] When Revue Devětsil (ReD) published a special issue on the Bauhaus in 1930, it included an article by Otti Berger entitled “Fabrics in Space.”[18] There, Berger describes the nature of textile material which constituted the main medium of her work. In her view, fabric can be characterized by structure, texture, facture and color.[19] This list already indicates the tactile nature of fabric. In a remarkable passage of her text, Berger says the following about it: “Most important in cloth is its tactility. The tactile in cloth is primary. A cloth should be grasped (gegriffen). One must be able to “grasp” (begreifen) [its structure] with the hands. The value of a fabric should above all be recognized tactilely, through the sense of touch. The understanding (Begreifen) of a cloth can just as well be felt with the hands, as a color can be with the eyes, or a sound can be in the ear.”[20] By repeating words and playing with their double meanings and their shifts, Berger accentuates the rhythmical and structural qualities of the text which almost assumes “textile” qualities. Berger writes as if she were weaving. The Bauhaus minuscules create a visually continuous surface of the text which unfolds in two columns as if it were two strips of fabric. Fabric is “constituted by two kinds of parallel elements; in the simplest case, there are vertical elements, and the two intertwine, intersecting perpendicularly. […] The two kinds of elements have different functions; one is fixed, the other mobile, passing above and beneath the fixed.”[21] The space of the fabric is “necessarily delimited, closed on at least one side: the fabric can be infinite in length but not in width, which is determined by the frame of the warp; the necessity of a back and forth motion implies a closed space […].”[22] Within this space, repetitions and semantic shifts lead to a tension between stability and change; the resulting text being both firm and flexible. The haptic act merges grasping and understanding whose interconnection is indicated already by the etymology of the German terms. Although Anni Albers studied at Bauhaus several years earlier than Berger, her book On Weaving was only published in 1965. In one chapter, she deals with “tactile sensitivity.”[23] According to Albers, the sense of touch is disappearing from the modern world which is getting filled with words and images. Industrial production has made our labor easier, however, it brings us out of touch with materials. Therefore we have to train our atrophied ability to touch.[24] Albers recommends us to touch various surfaces with blindfolded eyes, distinguish and compare them so we attain the ability to perceive the tactile qualities of matter and to be able to use them. Anni Albers does not limit “the tactile” to the sphere of the sense of touch either. She admits the possibility of creating an illusory tactile surface for instance by means of drawing, print or the typewriter. Such attempts, according to Albers, can help us in gaining “new terms in the vocabulary of tactile language.”[25] These terms are born when one kind of sensation is translated into another. This transmission also works between individual art disciplines and art media. Gottfried Semper mentions ancient Egyptian tombs whose walls were covered with geometrical decorations adopting the “morphology” of embroidery and fabrics.[26] However, even after transferring textile to architecture, the ornament has retained certain textile qualities: we can still discern “patterns, seams and hems.” The repetitive structure of an ornamental pattern covers the surface and thus makes a tactile impression, be it a sheet of paper, wallpaper or illusory painting of a room. The tactile liberates itself from its original material medium: the optical effect imitates fabric, thus opening up a new visual experience and enabling a touch by the eyes. As Berger puts it, material disappears through material.[27] A tactile potential is also present in media traditionally considered “optical,” such as photography, as shown by art historian T’ai Smith in her book Bauhaus Weaving Theory.[28] On the example of Otti Berger and László Moholy-Nagy, she has demonstrated how the terms of the tactile and the optical penetrated the period artistic thought. While Berger primarily emphasized the tactile quality of textile, Moholy-Nagy depicted photography as a highly optical medium. On the other hand though, in his experimental approach to photography, he refused its purely representative conception, as presented e.g. by his Bauhaus colleague Ernö Kállai. Whereas according to Kállai, photography, otherwise a faithful tool of reproduction of painters’ canvases, is unable to mediate the tactile qualities of painting,[29] Moholy-Nagy emphasized the facture and texture of photography itself, along with its certain “haptic” nature.[30] T’ai Smith demonstrates that a photograph of fabrics highlights the texture of fabrics: “Where tactility was the precursor to an optical Kunstwollen within Riegl’s teleology, the visual perception of texture, through photographs of textiles, became a precursor to the recognition of the tactility of fabrics.”[31] Photography becomes a sovereign tool of the close look, and as such, it reveals the depth of the surface, the structure, texture and facture of cloth. From Aristotle through Riegl and Wölfflin to Berger, Albers and Moholy-Nagy, Deleuze and Guattari, the same motif recurs: tactile experience somehow conditions optical experience, disappearing from it while remaining in it, limiting it while expanding it. One can nod to the statement that “haptic is a better word than “tactile” since it does not establish an opposition between two sense organs but rather invites the assumption that the eye itself may fulfill this nonoptical function.”[32] The close look rather corresponds to haptic than optical perception. The haptic is not bound to a particular sense organ, rather denoting a certain way of perception centered around touch. It is quite relevant to ask with Jacques Derrida whether eyes can touch.[33] The haptic is related – rather than to the tactile – to tact. Derrida understands tact “not in the common sense of the tactile” but in the sense of “knowing how to touch without touching, without touching too much, where touching is already too much.“[34] It is perhaps here that eyes touch. To do so, one has to look closely, not only in the spatial sense of the word. Nahsicht can thus assume other meanings: looking closely, seeing the close, seeing closeness, the closeness of seeing and the closeness of touch, the closeness of seeing touch. “We touch things to assure ourselves of reality. We touch the objects of our love. We touch the things we form.”[35] In each touch, we are touching and we are touched.[36] Each touch is also a touch of ourselves.[37]

Vojtěch Märc, May 2017

[1] Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, “1440 – The Smooth and the Striated,” in A Thousand Plateaus, London; New York: Continuum, 2004, pp. 525–526.

[2] Ibid, pp. 525–526.

[3] Aristotle, De Anima, Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing, 2012, p.99.

[4] László Moholy-Nagy, The New Vision: From Material to Architecture, New York: Brewer, Warren & Putnam, 1932.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Aristotle, De Anima.

[7] Alois Riegl, Die spätrömische Kunst-Industrie nach den Funden in Österreich-Ungarn im Zusammenhange mit der Gesamtentwicklung der Bildenden Künste bei den Mittelmeervölkern, Vienna: Österreichische Staatsdruckerei, 1901.

[8] Ibid, p. 18.

[9] T’ai Smith, “Limits of the Tactile and the Optical: Bauhaus Fabric in the Frame of Photography,” Grey Room VI, No. 26, 2006, p. 10.

[10] Heinrich Wölfflin, The Principles of Art History: The Problem of the Development of Style in Later Art, New York: Dover, 1950, p. 21.

[11] Ibid, p. 29.

[12] Ibid, p. 27.

[13] Moholy-Nagy, The New Vision.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Otti Berger, “Stoffe im Raum,” ReD III, No. 5, 1930, p. 143–145.

[19] Ibid, p. 143.

[20] Ibid p. 145.

[21] Deleuze and Guattari.

[22] Ibid.

[23] Anni Albers, On Weaving, Middletown, Conn.: Wesleyan University Press, 1965.

[24] Ibid, p. 63.

[25] Ibid, p. 65.

[26] Gottfried Semper, Die textile Kunst für sich betrachtet und in Beziehung zur Baukunst, Frankfurt am Main: Verlag für Kunst und Wissenschaft, 1860, p. 415.

[27] Berger, “Stoffe im Raum,” p. 145.

[28] T’ai Smith, Bauhaus Weaving Theory: From Feminine Craft to Mode of Design, Minneapolis, Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press, 2014, p. 79–110.

[29] Ernst Kallai, “Painting and Photography,” in Roswitha Fricke (ed.), Bauhaus Photography,Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1985, p. 132.

[30] Smith, Bauhaus Weaving Theory, p. 82–84.

[31] Ibid, p. 109.

[32] Deleuze and Guattari, “1440 – The Smooth and the Striated,”

[33] Jacques Derrida, On Touching: Jean-Luc Nancy, Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2005.

[34] Ibid, p. 67.

[35] Albers, On Weaving, p. 62.

[36] Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, Touching Feeling: Affect, Pedagogy, Performativity, Durham: Duke University Press, 2003, p. 14.

[37] Derrida, On Touching, from p. 6 on.